When Andy Warhol depicted a cow’s head for fifty years, he chose as his model an illustration from a brand for a milk product instead of a natural cow. “What’s the difference?” – he seemed to say. How can I believe a label that says the meat is 100% beef from Sweden when I buy shop at my local grocery store? I can’t tell it from its taste or appearance, but I have to blindly trust whoever claims it is true.

Whether I like it or not, I am directed to second-hand or third-hand information when deciding what is true or false, authentic or inauthentic. One of the most tangible effects of this development is our relationship with nature. Nature has either been a necessity for human survival or a resource for my own benefit or for the benefit of others. Today it is difficult to make the distinction.

Twenty years ago, chemist Paul Crutzen and biologist Eugene Stoermer came to a conclusion that the industrial use of natural resources and the human impact on the Earth’s environment is so significant that it justifies the introduction of a new geological epoch – the Anthropocene. According to the scientists, this era began with the invention of steam engine by James Watt in 1784.

In that regard, the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic reminds us that reality does not consist of goods to buy or objects to use, but rather of infinitely subtle variations of living interactions. The uncertainty, the pain, the deaths, and the economic and political crises that will occur sooner or later, remind us of a microscopic creature that has disrupted and infiltrated the whole . The pandemic is a lesson in our Anthropocene age – a lesson about the fragility of our global ecosystem.

But the pandemic can also be a wake-up call for the dangerous fools who dream of closed borders or who believe that the atmosphere can be nationalized. But it can also bring back a famous thesis of anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss’s who said, “art is also a guide, an instrument of teaching and learning of reality that surrounds us.”

Art theorist Nicolas Bourriaud developed his idea of relational aesthetics in the 1990s. It featured the term “totemism”, sometimes also referred to as “animism”. It refers to a way of social organization based on the idea that there is a link, a common essence, between an individual human being (or a group) and the environment (animals, plants, atmosphere).

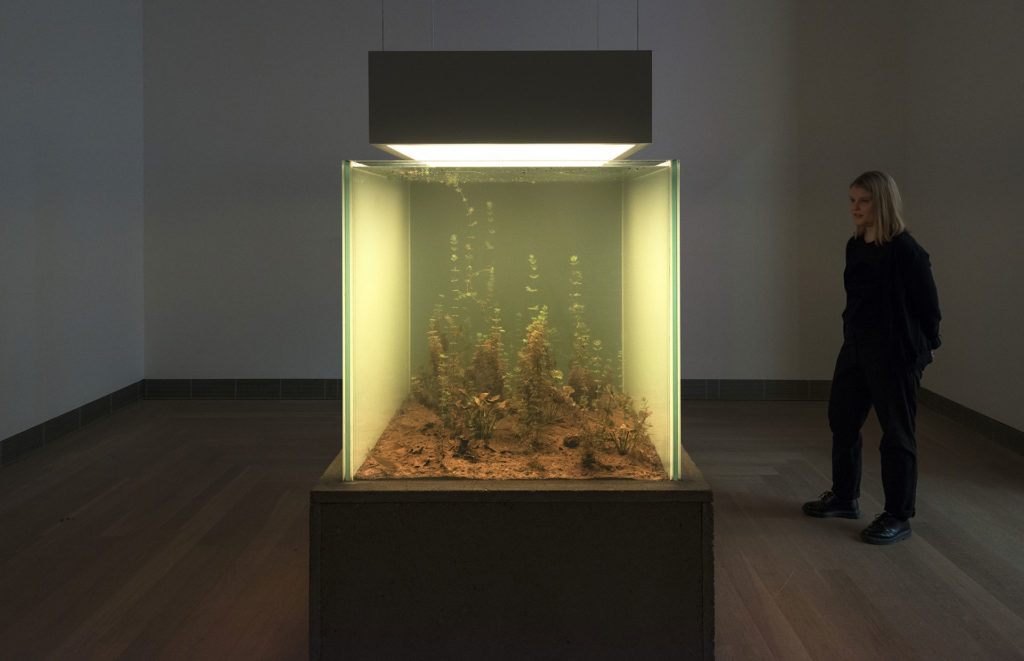

Live pond ecosystem, light box, switchable glass, concrete. 184,5 × 138,5 × 103,7 cm. Photo: Åsa Lundén/Moderna Museet

One example of this can be found in Moderna Museet’s collection – “Nymphea’s transplant (autumn 1917)” created in 2014 by Pierre Huyhge. The starting point for the work were artificial ponds in Giverny that Claude Monet used as models for his paintings of water lilies. By extracting samples of the water, Huyghe transplanted the pond’s flora and fauna into an aquarium that mimicked the weather and light conditions of Giverny between 1914 and 1918.

Monet’s ponds were designed to comfortably provide him with lilies and one can interpret Monet’s paintings as depictions of nature shaped by man. In Huyghe’s case, nature is a living organism. Unlike Monet’s lilies or Warhol’s cows, both of which are an association of reality and fiction, true or false, Huyghe’s living organism is an implicit argument that art is no longer ett simulacrum – the artist is no longer an observer but an active participant of nature. Through the work, Huyghe points out that there is a link, a dynamic continuity, between people and their environment, something that is at the heart of both the climate crisis and the disaster of the current pandemic.

Are humans themselves guilty of the threats to humanity? Over the centuries, we have seen art describe the horrors of life and appeal to gods, ideologies or science in response to various threats. There is nothing wrong with that, but I am also thinking of Winston Churchill’s answer once requested to spend more money on the military during WW II: “There is no more money! “. When the generals argued that he should take money from culture, Churchill replied: “What are we going to defend?”.

During the coronavirus crisis, we have seen an amazing struggle to continue the culture’s presence in our communities despite the closure of museums, concert halls, theatres, libraries, and cinemas around the world. What the pandemic has taught us, is that for many people culture is not a dessert, but the main course.

There will come a time when everything returns to normal. Or will it!? Every day we hear and read that the world will not be the same when the crisis finally subsides. What comes to my mind yet again, is the fragility of existence itself. At best, more people will understand that the concept of the Anthropocene is not a buzzword, but the reality live in and take joint responsibility for the world we share, whether they live in a favela in Rio de Janeiro, or a luxury hotel in New York.

The crisis has also raised questions about, for example, the future of art galleries and museums. In an article published in the online magazine Artnet (April 14, 2020), cultural strategist Andras Szanto predicts that there will be fewer blockbuster exhibitions due to the increased cost of international loans, transport, couriers, insurance fees, and the raising awareness of the climate footprint they entail. Instead, he predicts that there will be innovative stories based on the museums’ permanent collections or exhibitions focusing on current themes that may interest a wide audience. Perhaps, the crisis will even serve as wind that blows in the sails of a new museology, in which public engagement becomes as important as managing of exhibits? The Museum of Modern Art is no longer a temple on a hill that conveys knowledge and prestige to the well-established, but is rather a more open and participatory institution that engages the audience and offers a sense of transcendence, continuity, and belonging, Szanto pointed out.

It is not possible to predict the future, but there is something comforting in Szanto’s reasoning. Wesaw before and continue to see how both the high and the popular culture brings people together, despite curfews and quarantine. We see how old friendships are being tested and new ones are emerging.

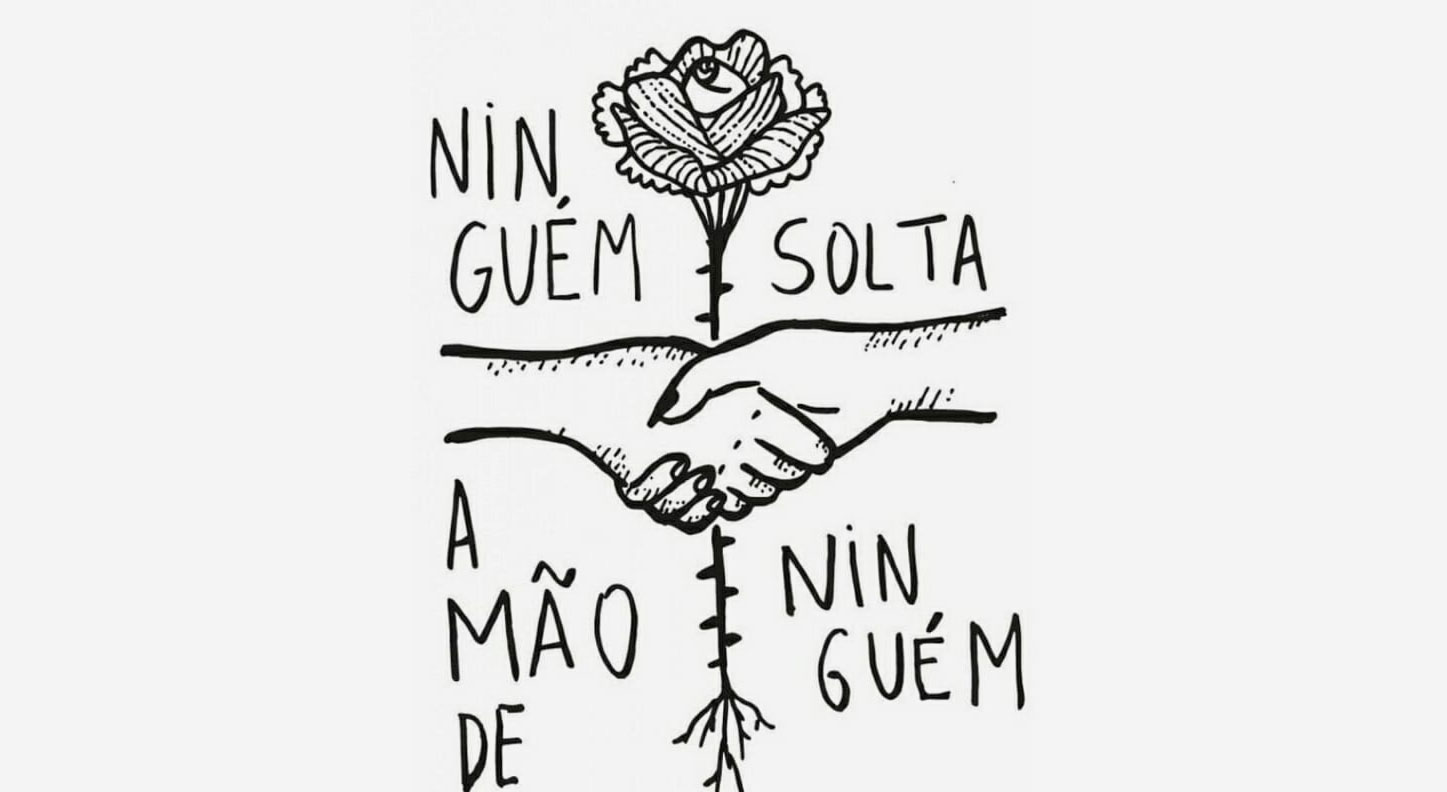

“Ninguém solta a mão de ninguém” is a meme from Brazil that has been spreading viral around the world for some time, but with a completely different meaning than Covid-19. Originally it was a tattoo created by Thereza Nardelli, directed against the policy of the Brazlian president and former military officer Jair Bolsonaro. It depicted two intertwined hands with a flower in between, accompanied by a phrase, which in English can be translated as: “No one let go of anyone’s hand”.

Perhaps not the best call for social distance, but you understand what I mean.