Group exhibition by Study in English programme students and exchange students of the University of the Arts Poznan

Organizer: University of the Arts Poznan

Organizing Committee:

Aniela Perszko – curator

Mateusz Bieczyński

Szymon Dolata

Artists:

Weizhi Chen (China), University of the Arts Poznan

Shuwen Jia (China), University of the Arts Poznan

Yi-Ho Li (Taiwan), Shih Chien University

Yujia Shi (China), University of the Arts Poznan

Ana Sanchez Valverde (Spain), Universidad de Granada

Emanuel Soopaya (France), Université Rennes 2

Adela Suchankova (Czech Republic), University of Ostrava

Marine Troadec (France), Université Rennes 2

Since its very first edition in 2017, the exhibition Made in.between has been dedicated to works by international students of UAP, that are selected in the course of open call. Through the exhibition, students have a chance to talk about their feeling of isolation and the struggle to find themselves in a new environment. Students who come to UAP from other countries often feel that they are caught up between two worlds – the world of they know and the world they need to adjust to. This year, due to the coronavirus pandemic, the feeling of isolation and solitude are even more widespread. After all, the whole world does not function as it used to. The pandemic does not only concern people who live far away, but it has affected as all, our society, and our mental state. Many of our students decided to leave their home countries to spend a semester or they whole study periods at UAP. For them, the crisis caused by the coronavirus that involved closing of borders and cancelling flight has led to an even stronger sense of isolation. They can neither leave their temporary homes in Poznań, nor go back to their home countries.

As the main theme of this year’s edition of Poznań Art Week is ‘’Remedy”, we decided to ask international students of UAP to reflect on the role of art in the time of pandemic. Works submitted for the exhibition were created during the period of isolation or relate to it. They all present universal matters and feelings that could be experienced during the epidemic: the silence, social distancing, fear, longing, and nostalgia. Such feelings are universal and everyone can related to them, regardless of nationality and place or residence.

When the epidemic broke out, SILENCE and images of deserted cities were one of the first messages that reached viewers around the world through mass media. Wuhan, Milan, New York – big cities that are normally crowded with tourists, suddenly turned into apocalyptic ghost towns. The view was striking not only visually. The total silence was equally shocking. We suddenly could not hear the pedestrians and cars. Cafes, music halls, ad clubs went silent as well. Silence also dominated our homes, as we were not allowed invite any guests. Silence, though strange and uncomfortable, became a new space in which our senses could detect more – not the sensory stimuli, but the phenomena that we used to ignore due to overstimulation. Weizhi Chen shows this in a quite grotesque way in her work Listening. According to the author, ‘’everything is speaking during quarantine”. It is the environment that tries to communicate with us, not the other way round. On the other hand, when the social life is on hold, we crave interaction and we look for echoes of our activities among other, newly defined ‘recipients’. The video by Marine Troadec entitled Circle is based on schematic and symbolic sketches of another artist– Shuwen Jia. The video is a form of narration of everyday life in the time of pandemic, its ‘circle’. Wilted flowers and empty dishes are symbols of a pause, while everyday sounds (a plane, sounds coming from the flat) create a soundtrack of life during lockdown. At the seaside created by Yujia Shi is a pantomime that captures the phenomenon of silence in a different way. The artist visualizes in his own apartment activities normally attributed to completely different circumstances – e.g. at the beach one can always hear other people, the sound of crashing waves, the screeching of seagulls. For Yujia Shi the silence has a dual meaning – it also allows us to contemplate whether sounds we know from the past are ever going repeat, and to think if, after we return to normality, we still be able to experience places in the same manner as we used to.

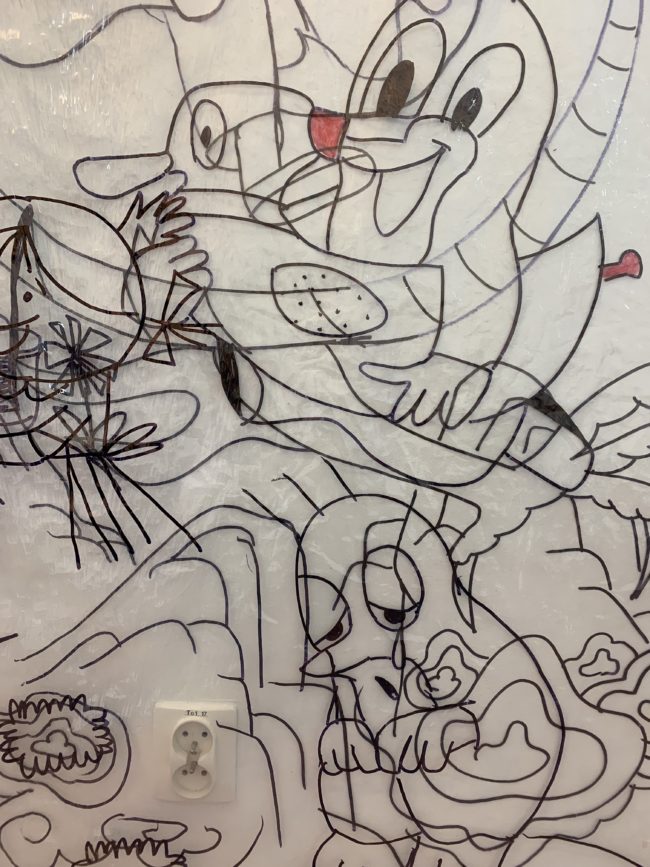

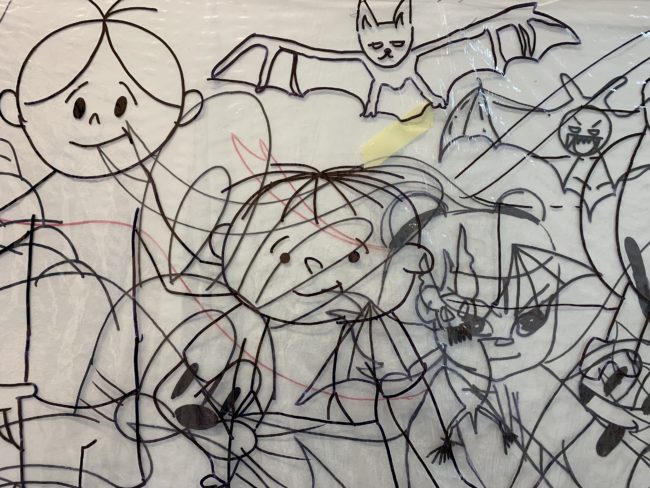

Shuwen Jia – sketches to the video Circle by Marine Troadec

SOCIAL DISTANCING that was imposed on us by governments is a completely new form of isolation. Keeping an appropriate distance between people has completely changed our point of view. We are no longer co-participants, but we have become observers. The physical distance can intensify human relations – we pay more attention to verbal contact. In the physical aspect, however, we still prefer not to get to close to each other. As we remained at home for most of the time, the view from our windows became our point of reference, a peephole into reality we could not participate in out of health reasons. This is reflected in another work by Yujia Shi entitled Yong E. An observer is silently looking at passers-by, flanerie being replaced by voyeurism. The video by Shuwen Jia Wish I could fly expresses not only the desire to return home, but above all the inability to cope with restrictions. The author uses a simple paper plane to oppose travel restrictions. On the other hand, the word home written on the paper plane is a reference to home address or flight ticket. It is a modern day message in a bottle sent by a traveler stranded on a desert island.

ANXIETY felt in a new situation, although very individual, coincides in two points. On the one hand, death statistics and information about the invisible enemy (the virus) lead to constant fear, concern with the health conditions of the loved ones, and anxiety about being trapped in a foreign country We were knocked out of our natural rhythm and forced to dynamically organize our everyday lives based on latest news. In this context, a diary becomes a powerful form of keeping track of the reality. In her video diary Mar.12-May.4, 2020, Yi-Ho Li uses a balloon as a tool to speak about of her life in the time of confinement in a student dormitory. She also explains its cultural symbolism. The balloon becomes a metaphor for an object that could freely fly high in the sky, but instead is trapped in a room. On the other hand, the balloon symbolizes celebration, and is an object of artistic activity of students that integrated during lockdown.

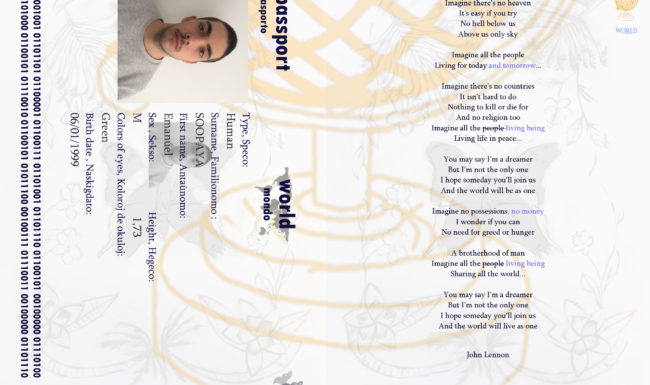

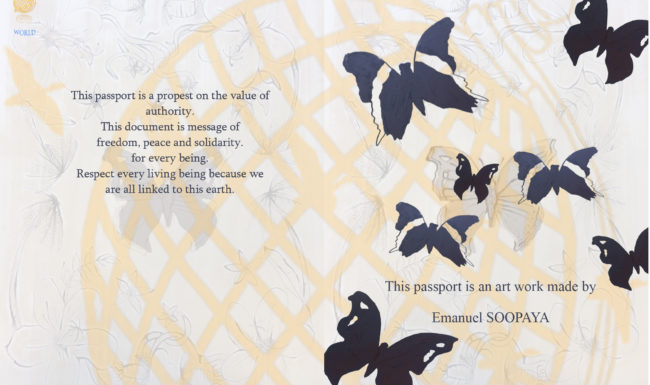

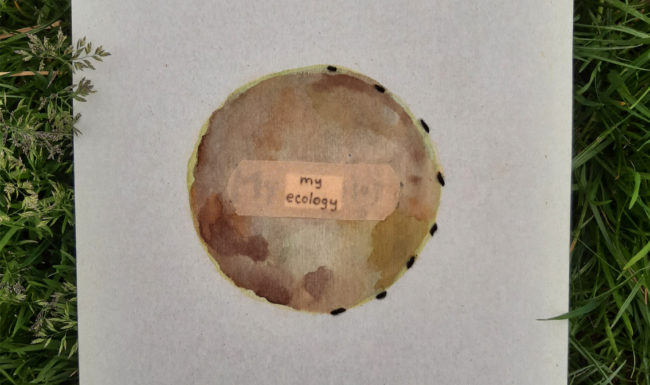

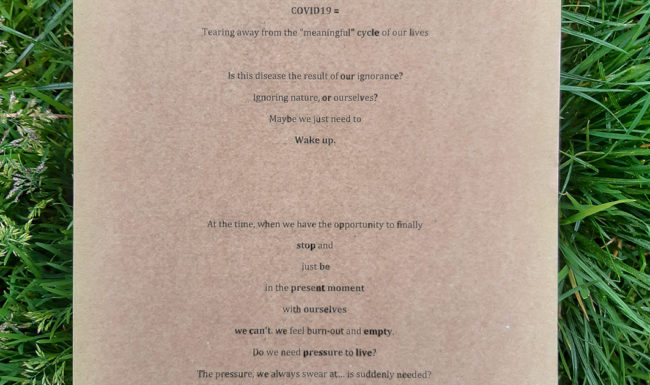

World Passport by Emanuela Soopaya and My ecology by Adela Suchankova address anxiety and fear from a different perspective. In their works, they reflect on to the questions that the whole world has been asking – what will the “new normality” look like? What were the reasons of the current pandemic and climatic crisis? Both artists make references to two spheres – the micro and macro environment, emphasizing the essence of individual actions as a basic factor necessary to change the global state of affairs.

Emanuel Soopaya (France), World Passport, digital drawing, 8,8×12,5cm, May 2020

Adela Suchankova (Czech Republic), My ecology, book (chosen pages), mixed techniques, 21×29,7cm, May 2020

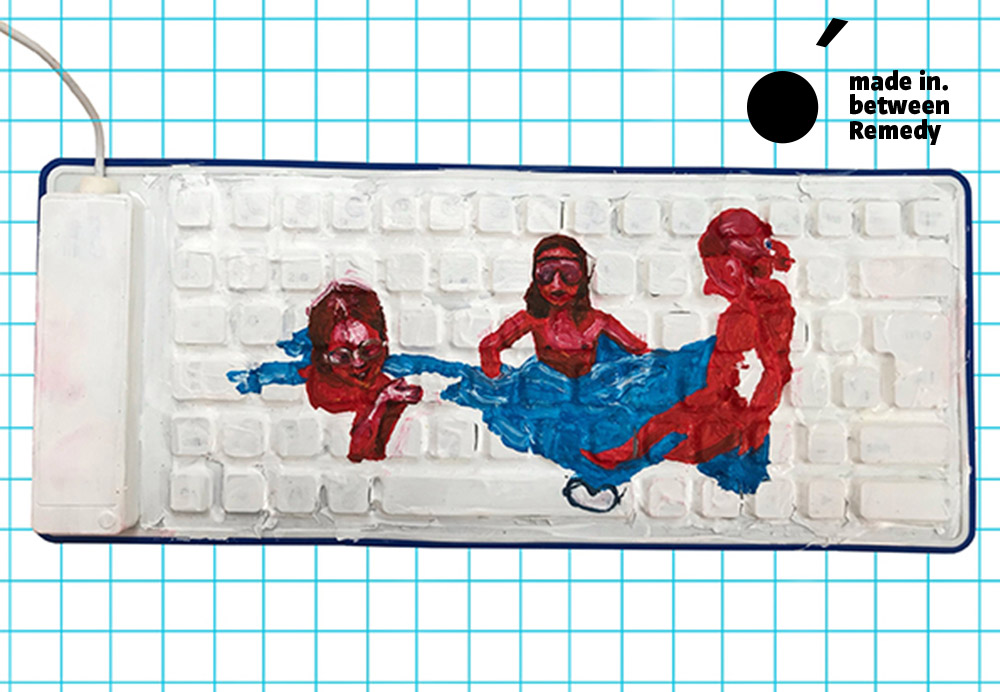

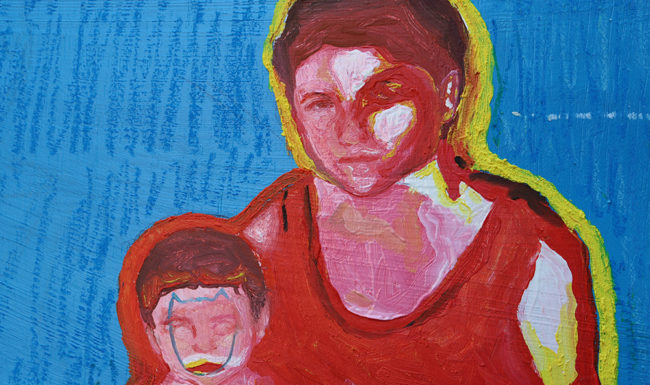

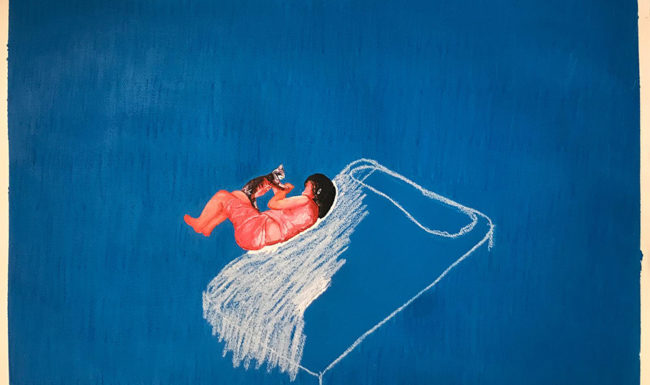

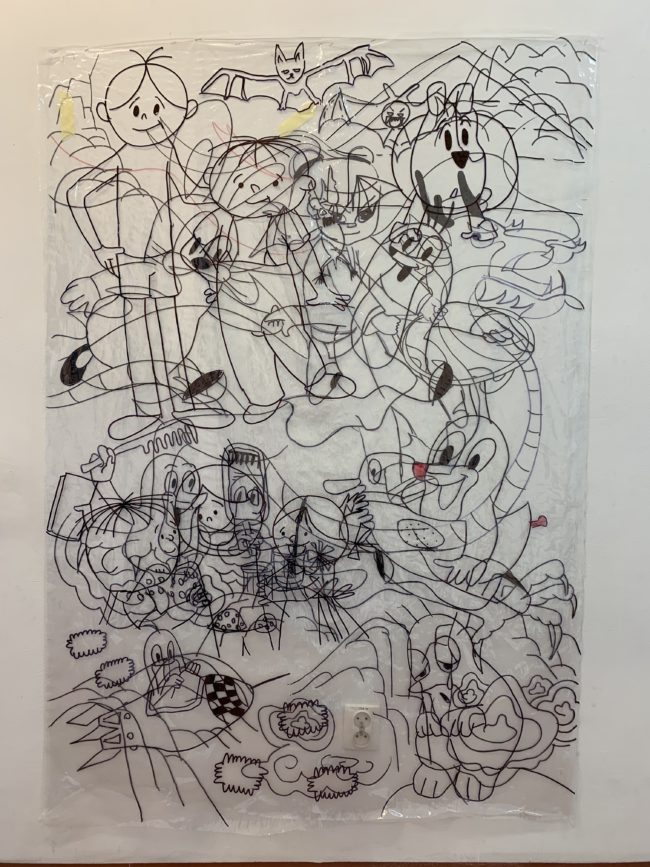

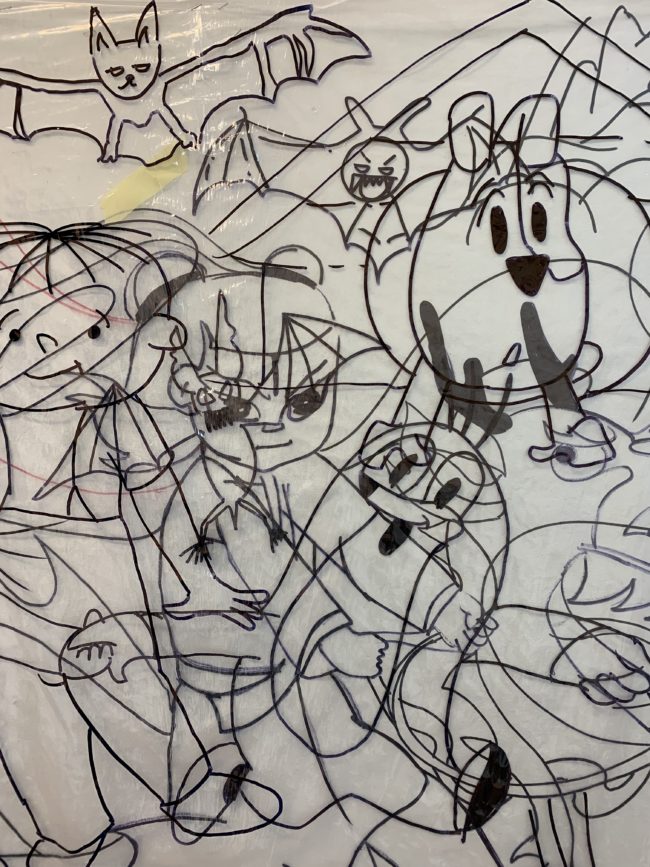

LONGING seems to be the most universal feeling during isolation, regardless of the cultural background, set of views, or the things we long for. Quarantine might be perceived as the time when we long for currently unavailable things (physical contact, regular ways of working, travelling). However, isolation can also evoke emotions that we normally try to conceal. Silence and lack of stimuli allow us to analyze our past and future. Paintings by Ana Sanchez Valverde are based on the artist’s childhood memories, her old photographs and drawings. This transfer of past images to current works, created with the use of an experimental medium, is a personal link between the time of carelessness and innocence and the current state of isolation (also from artistic possibilities and inspirations). In her work One world, Shuwen Jia makes a similar reference. Her work depicts characters from Chinese, Polish, and Czech cartoons that overlap on a transparent foil. Jia’s work highlights the positive emotional impact of childhood memories. It also shows that they can be easily recalled, even if now we are very far from our childhood homes.

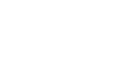

Ana Sanchez Valverde (Spain), Bathing in the pool, oil on computer keyboard, 10x25cm

Ana Sanchez Valverde (Spain), Playing in the bathtub, oil and pastels on wood, 80x120cm

Ana Sanchez Valverde (Spain), Sleeping with my cat, oil, pastels on watercolour paper, 50x70cm

Shuwen Jia (China), One World, marker pen, plastic foil, 100x150cm, February 2020

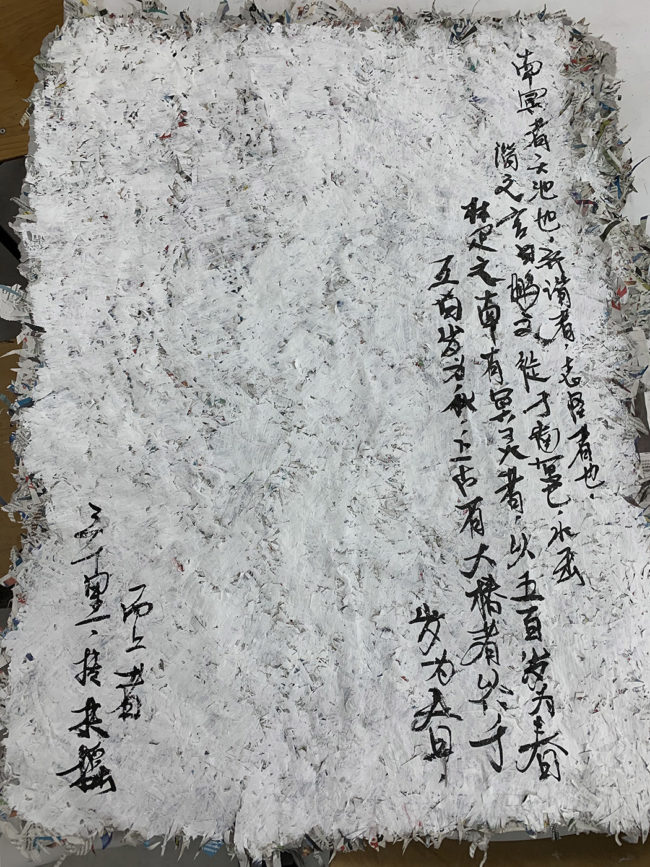

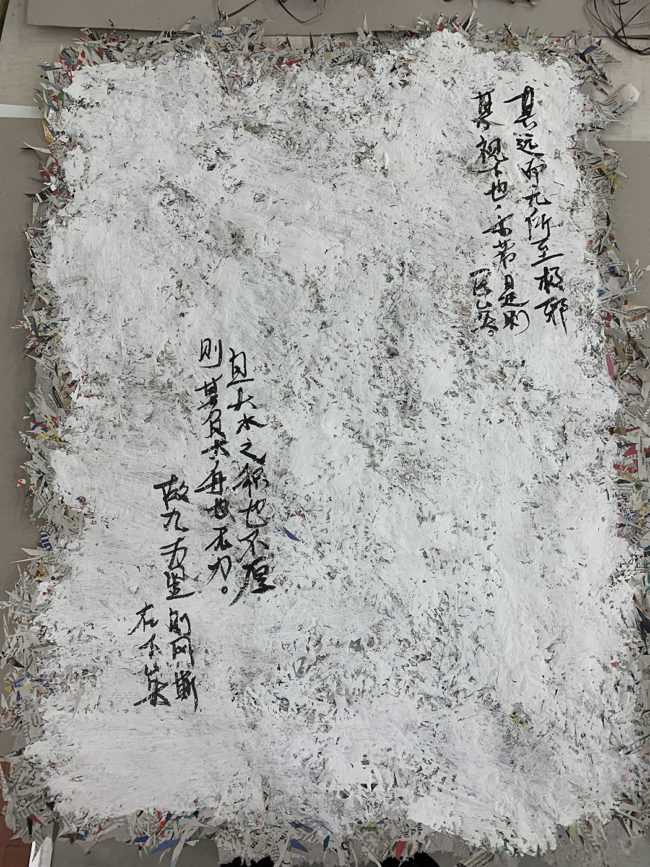

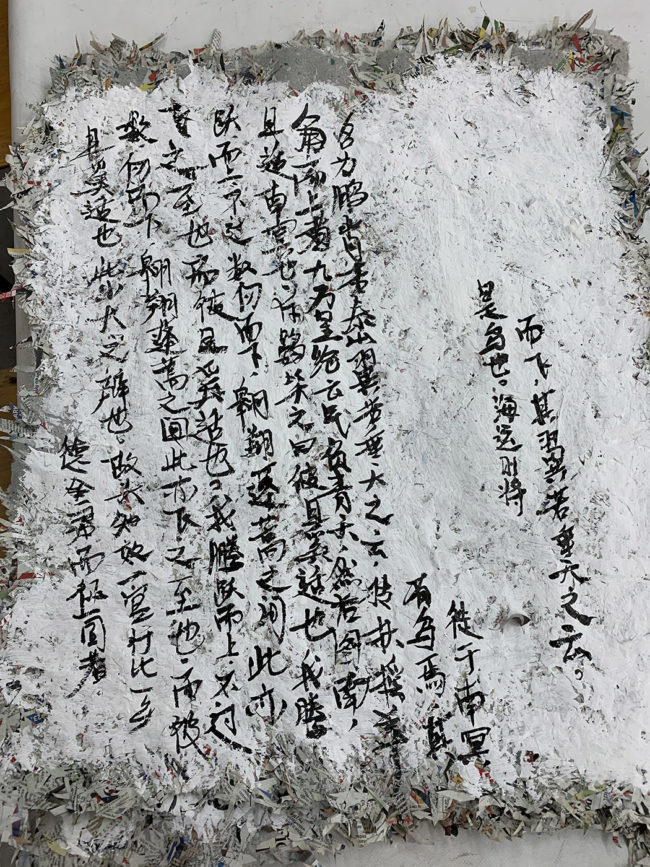

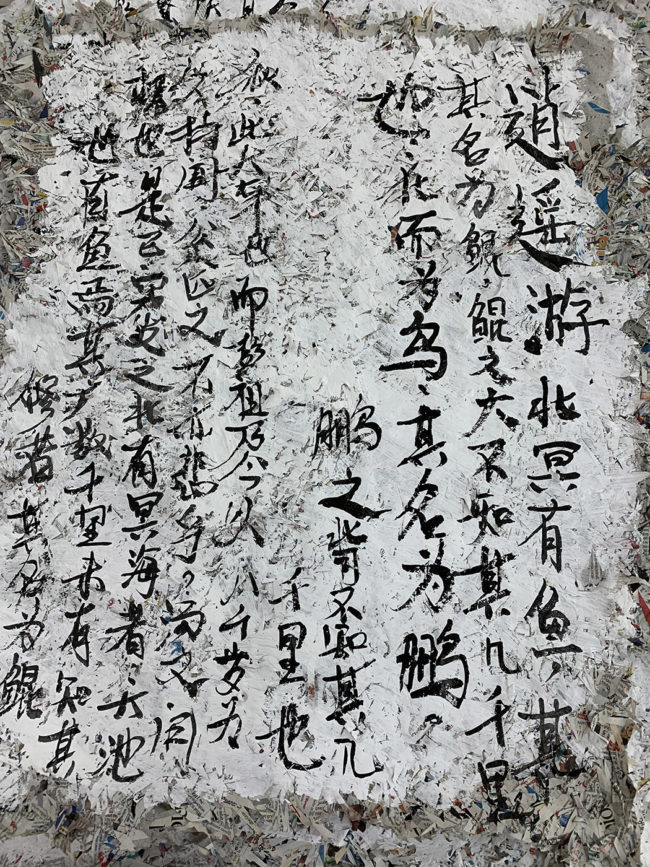

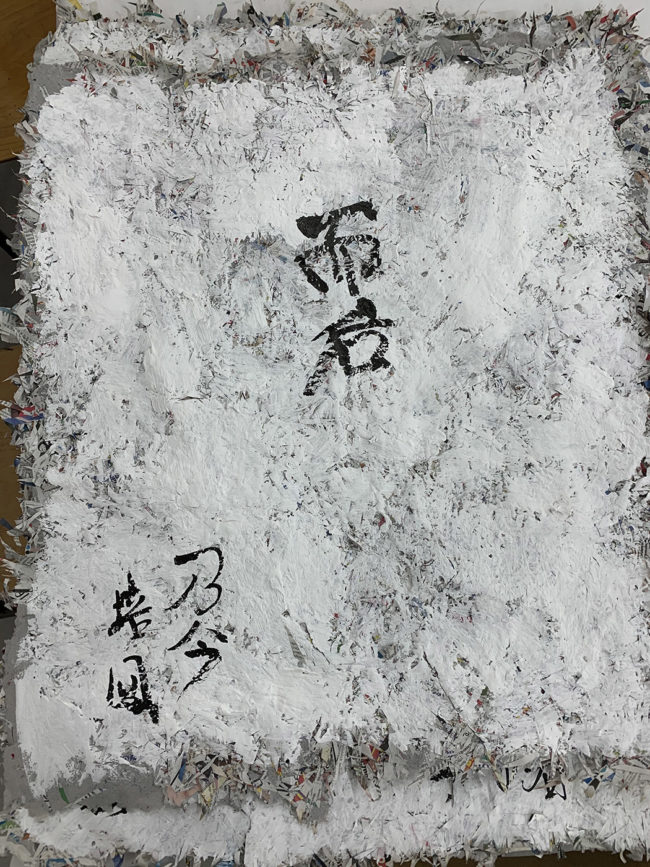

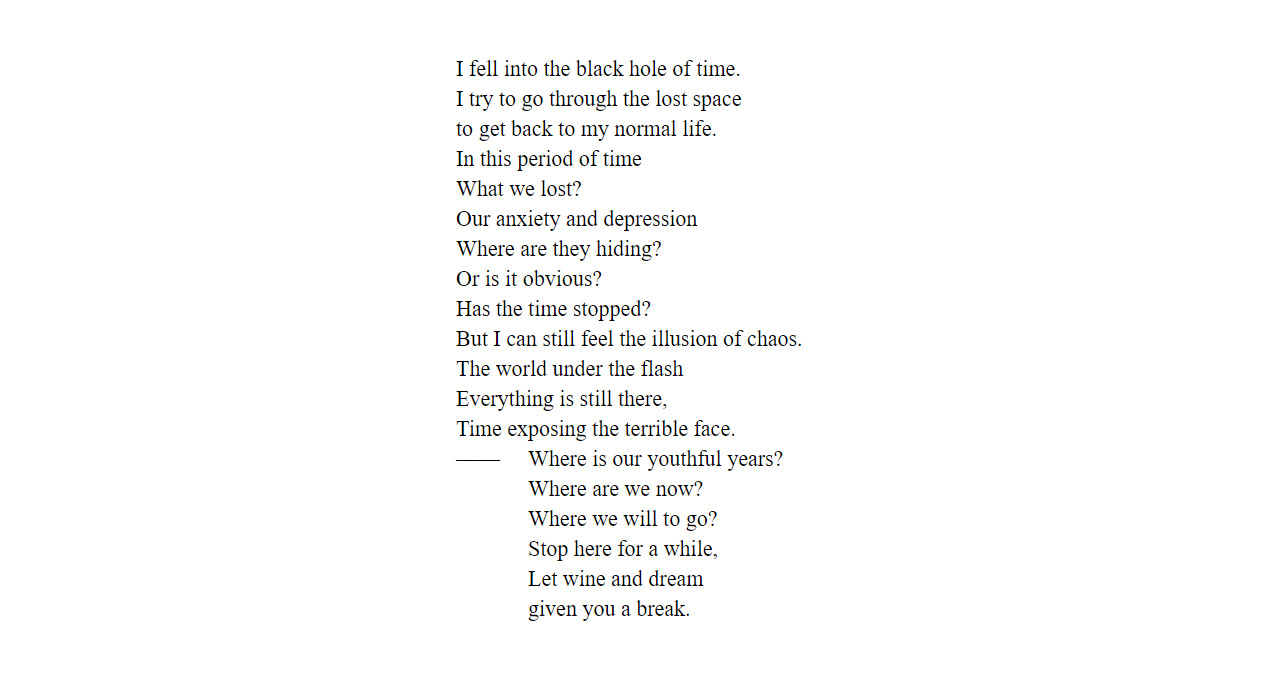

Difficult issues addressed by our students in works submitted for the exhibition seem quite depressing. However, they manage to show a certain universality of the situation. They unify and reduce it to a very general but common denominator. Another video work by Yujia Shi It’s not the spotlight becomes a visual metaphor of emotional state we have found ourselves in – we all try to navigate through these uncertain circumstances and seek for answers for difficult, yet universal questions. In the work entitled 逍遥游 Xiao Yao You, Shuwen Jia uses Chinese characters to present fragments by the Chinese philosopher Zhuang Zi who lived in the Warring States period (475 – 221 BC). The artist wrote the characters on papier mâché made of Polish newspapers. Two languages and cultures collide, which, given the current situation, gains a new context. Jia deliberately erased one message and replaced it with another, totally different in form and content. In place of dry daily news that we assimilate as quickly we forget, she inscribed a message that has existed for over two thousand years.

Yujia Shi (China), It’s not the spotlight, video, May 2020, You know what I mean, photographs, May 2020

Shuwen Jia (China), 逍遥游 Xiao Yao You, Chinese ink, papier mâché, 100x65cm, February 2020

Perhaps this solution could become a remedy in the time of pandemic – a cure for the discomfort caused by any of the physical, emotional, or social problems addressed by the works. Adapting a different, unconventional point of reference and shifting one’s perception to another level, while remaining fully aware of the current crisis, could allow us to keep distance not connected with alienation. The distance that could become a space for a deeper understanding of the world that surrounds us.

Aniela Perszko